Introduction

Commercial/military aircraft engines often have to operate in a dust environment. The presence of sand particles has a detrimental effect on these engines structurally and aerodynamically (Tabakoff et al., 1996). The engine air particle separators (EAPS) are often adopted to reduce the amount of sand particles ingested into the engine. Typical EAPS can be divided into three categories: vortex tube separators (VTS), inlet barrier filters (IBF), and inertial particle separators (IPS). In contrast to VTS and IBF systems, the IPS systems are usually integrated with the engine, which results in a more compact system and lower total pressure loss coefficient (Barone et al., 2015).

Accurately predicting the trajectory of the sand particles is critical for designing IPS because the air and sand particles experience different degrees of turning due to the differences in inertia inside the IPS flow path. According to the literature (Duffy and Shattuck, 1975a), the inlet particle concentration of IPS is about 0.05–2 g/m3, which leads to a tiny mass fraction so that particle-particle interactions and the effects of the particles on the air can be neglected. Thus, the discrete particle model was mostly used to predict the sand particles’ trajectory.

Numerous investigations have been performed on the IPS. Duffy and Shattuck (1975a) conducted a series of designs and experiments based on T700 IPS. They evaluated the influence of flow path geometry, pre-swirl, and de-swirl blades on the separation efficiency and total pressure loss coefficient. It has also been observed that the separation efficiency and total pressure loss coefficient were increased with the increment of the scavenge ratio. Ye et al. (2007) summarized the design procedure of IPS and pointed out that increasing the curvature of the outer flow path can promote sand particles to rebound into a scavenge flow path, thus increasing the separation efficiency. In another study carried out by Wu and Wang (2006), the separation efficiency was increased when the radial position of the splitter lip went down. The effect of different scavenge ratios on separation efficiency was investigated by Barone et al. (2015). They observed that when the scavenge ratio decreased, the separation region grew larger, and the separation efficiency was reduced. Hamed (1982) studied the effect of the sand particles’ diameter on the particle separation efficiency and explained the separation mechanism of particles with different diameters.

The above research mainly focuses on how separation efficiency varied according to the design parameters, but few studies (Hamed et al., 1995; Xu and Chen, 2021) focus on the accuracy of the numerical simulation itself. The present investigation aims to systematically identify the influential factors in numerical simulations that would affect the calculated particle separation efficiency, thus providing a guide to improve the simulation accuracy.

Methodology

Testcase

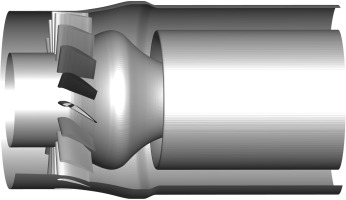

In this study, the IPS with pre-swirl blades described by Duffy and Shattuck (1975a) has been adopted. The main design parameters of the IPS are given in Table 1 and the sketch of the IPS geometry is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Main design parameters of the IPS.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Core mass flow (kg/s) | 2.268 |

| Scavenge ratio (SCR) | 16.90% |

| Total pressure loss coefficient | 0.0172 |

| Number of pre-swirl blades | 18 |

The total pressure loss coefficient (T.P. Loss) and separation efficiency are the most critical parameters to evaluate the performance of the IPS. The T.P. Loss is defined as follows:

where

The separation efficiency is calculated as follows:

where

The scavenge ratio (SCR) which reflects operating conditions, is expressed as follows:

where

Numerical method

The IPS's particle separation characteristics are simulated using the gas-solid two-phase flow method. The flowfield inside the IPS is obtained by RANS simulations, and then the discrete particle model is used to predict the trajectory of sand particles.

Gas phase method

The flowfield inside the IPS is simulated using an in-house CFD code named MAP (Multi-purpose Advanced Prediction code for fluid dynamics). The detailed description and validation of the code can be found in (Ning, 2014). It solves the integral form of governing equations discretized in space using the cell-centered finite-volume method. The advective fluxes are evaluated using the LDFSS scheme (Edwards, 1997) coupled with MUSCL interpolation to obtain high-order spatial accuracy. The diffusive fluxes are solved using traditional central differencing. The one-equation Spalart-Allmaras turbulence model with near-wall correction (Ning and Xu, 2001) is used for turbulent flows, which is discretized and solved in a coupled manner with the mean flow equations. Message Passing Interface (MPI) is used to parallelize the code. The discretized system is solved using the matrix-free Gauss-Seidel algorithm (Luo et al., 1998).

Concerning the boundary conditions, total pressure, total temperature, and flow angles are specified at the inflow boundary, whereas static pressure, considering radial equilibrium, is specified at the outflow boundary. Then, the 1D non-reflecting boundary condition method is applied. Non-slip and adiabatic conditions are employed for the solid walls. A mixing plane model based on flux conservation (Du and Ning, 2016) is used at interfaces between upstream mesh blocks and downstream mesh blocks with different pitches.

Particle phase method

In particle modeling, the discrete particle model was used, in which each sand particle is treated individually as a mass point. Neither the effect of the sand particle phase on the gas phase nor the effects between sand particles are considered. The drag force due to gas is regarded as the most important force, and other forces such as buoyancy force, pressure gradient force, Basset force, virtual mass force, Saffman force, and Magnus force are neglected (Lei, 2020).

The equation of motion of a sand particle in a relative rotating coordinate system is established as:

where

where

When a sand particle collides on a solid wall, it is assumed unbreakable and its rebound velocity vector is computed using empirical correlations given by Niu (2017). Restitution ratios of normal direction

where

Table 2.

Values of empirical parameters of restitution ratios.

An irregular particle drag coefficient model is used to predict a particle’s trajectory more accurately than the simple spherical drag model. The Corey Shape Factor (CSF) proposed by Connolly et al. (2020) is applied to characterize the shape of a particle. CSF is bound to 0 < CSF ≤ 1, while CSF = 1 indicates an aspect ratio of 1 in all three orthogonal planes (sphere), and CSF close to 0 indicates a very thin disk or plate. Their particle shape corrections are expressed as follows:

where

where Reynolds number of spherical particle

where

Irregular particles undoubtedly have lighter mass than spherical particles with the same maximum outer diameter. A new parameter Z is defined as the mass ratio of irregular particle to spherical particle. Apparently, Z = 0 when CSF = 0, and Z = 1 when CSF = 1. Statistical data shows that for sand particles, Z is in the range of 0.50 to 0.53 (Duffy and Shattuck, 1975b), while the averaged CSF is about 0.55 (Connolly et al., 2020). Thus, we propose the following approximation, which can be seen as a first-order linear fitting of

Using this correction, the mass of a sand particle is calculated by:

In this paper, the solid wall material is taken as an aluminum alloy. Sand particles are selected as quartz, and the density is 2,650 kg/m3, satisfying both the requirements of diameter (coarse Arizona road dust, known as AC-Coarse sand) and CSF distribution (Connolly et al., 2020), which is listed in Table 3. During computations, sand particles are randomly released at the inlet plane with the axial velocity equaling 80% of the gas velocity. When a sand particle passes through the interface, its radial position remains unchanged while its circumferential position is reset randomly. The vaneless scavenge flow path domain's length is twice the original length, and its sector angle is 2 degrees.

Table 3.

Details of AC-Coarse sand particle.

During the experiment, the uncertainty of separation efficiency due to the incomplete collection of sand particles (Barone et al., 2015; Xu and Chen, 2021) and the ambiguity of sand particle’s diameter (Duffy and Shattuck, 1975a) would be about 1%. As for computation, in addition to errors due to the discretization error of the governing equation and the error of the empirical model, there are also random errors caused by random parameters, such as the diameter distribution of sand particles, release position, and rebound effects. Considering the impact of these random factors, more than five calculations are conducted to get the mean value and standard deviation for each set of calculation input parameters.

Results and discussion

Method validation

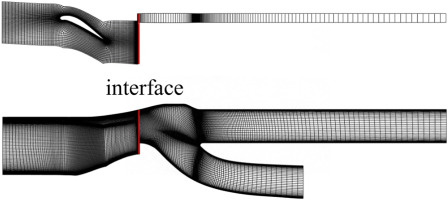

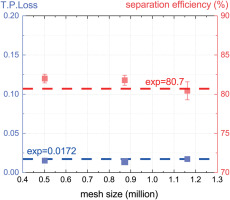

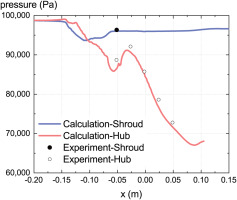

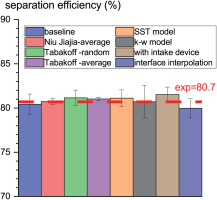

The computation mesh of the IPS is shown in Figure 2. Firstly, the mesh independence of the IPS’ separation efficiency and total pressure loss coefficient is verified using mesh sizes of 500,000, 870,000, and 1,160,000, as shown in Figure 3. The width of the error bands in Figure 3 are four times the standard deviation, the same hereafter. The calculated separation efficiency and total pressure loss coefficient are 80.43% ± 1.148% (mean ± 2 × standard deviation) and 0.0171, respectively, when the mesh size reaches 1,160,000, and the measured value is 80.7% and 0.0172, respectively. Thus, the baseline mesh size is determined to be 1,160,000, as shown in Figure 2. Figure 4 also indicates that the calculated static pressure distribution on the shroud and hub wall matches the measurements well. These results indicated that the adopted gas-solid two-phase method described above is reliable.

Particle trajectory analysis

The fluid domain inside the IPS includes an inlet, a scavenge flow path, and a core flow path. The solid structure consists of a shroud, a hub, and a splitter. Air can turn smoothly towards the core flow path, while sand particles tend to move closer to the shroud and enter the scavenge flow path due to greater inertia.

From the perspective of dimensional analysis of the motion equation of sand particle Equation 4, the mass of a sand particle is proportional to volume (cubic of diameter) while drag force is proportional to characteristic area (square of diameter). Thus, the effect of drag force acting on small-size sand particles would be more significant. It can also be seen from Equation 12 that

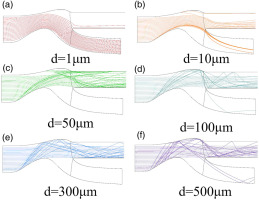

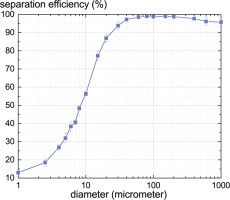

As the computation results are shown in Figures 5 and 6, the separation efficiency of sand particles with a diameter smaller than 10 μm is low because smaller sand particles are more tented to enter the core flow path together with air. For sand particles with a diameter larger than 30 μm, nearly all of them can be separated due to the dominance of inertial force, while unseparated sand particles are mainly rebounded by the hub and the shroud and then move into the core flow path.

Sensitivity analysis

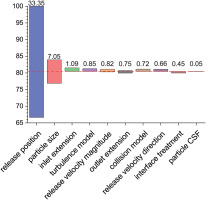

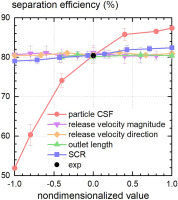

The parameters that would affect the separation efficiency can be classified into two categories: (1) computation input parameters, such as the physical property of a sand particle, the release condition, extension of the computation domain, and the selection of operating condition (SCR); (2) computation methods, such as turbulence model, rebound model, and interface treatment. The variation range of the separation efficiency due to the change in the above parameters is shown in Figure 7. The exact definitions and variation ranges of these parameters are explained in detail in the following subsections.

Computation input parameters

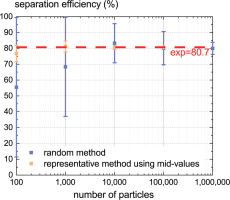

Sand particles’ diameter distribution is crucial to gain accurate computation results because total separation efficiency is essentially the weighted mean of separation efficiency of different diameters. A straightforward way to determine particles’ diameters is by randomly setting each particle’s diameter according to a given probability distribution. However, the results would converge to a specific value only if a sufficient number of particles were simulated, which would be beyond the available computation resources. Another easier but reasonable way is to limit the particle diameters to finite representative values and then calculate total separation efficiency as the weighted mean of separation efficiency at these representative diameters. Computation results using mid-values of subintervals as representative diameters conform to the experiment data very well (as shown in Figure 8) while using the upper bound or the lower bound of subintervals as representative diameters would produce about an error of 3% in separation efficiency for AC coarse sand.

Results in Figure 8 also show that the separation efficiency can’t be predicted accurately even when the number of particles reaches 106 using the random method, while 104 particles seem enough for the representative method to get an adequately accurate result. Hence, the representative method using the mid-value of the subintervals and particle number of 104 is adopted hereafter.

Figure 9 shows that as a representative value of CSF varies from 0.01 to 1.0 (nondimensionalized to [−1,1], the same hereafter), the particle's inertia increases, and thus separation efficiency rises. Both results of the random and representative methods using CSF = 0.5 agree well with the experiment data.

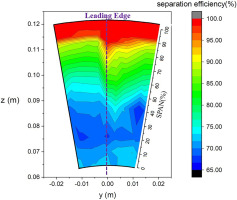

While mean particle release velocity magnitude varies from zero to twice the gas velocity magnitude and particle release velocity direction randomly varies from axial to radial with the average direction of axial both have little impact on separation efficiency, particle release position does have a significant effect on separation efficiency, as shown in Figures 7 and 10. The non-uniformity of separation efficiency mainly occurs along the radial direction, affected by the relative position of the scavenge flow path and the core flow path. The higher separation efficiency would be achieved when the sand particle was released closer to the shroud. Besides, there is a certain degree of non-uniformity in the circumferential direction near the leading edge due to the existence of the pre-swirl blades. The difference in separation efficiency between different release positions is as high as 33.35%, as shown in Figure 7, indicating special attention should be paid.

Figure 10.

Separation efficiency distribution when sand particles are released at different radial positions.

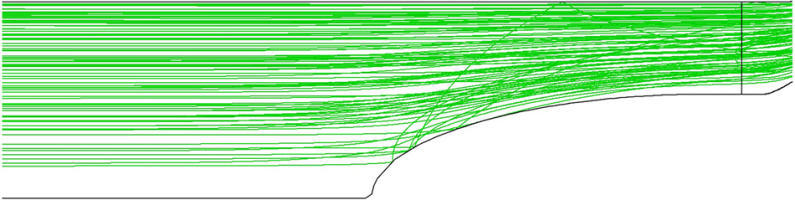

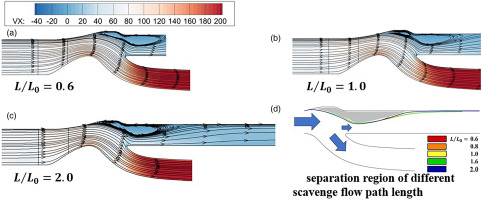

The influence of the bullet-shaped intake device's existence has been proven to be small, as shown in Figure 11. Although the distribution of sand particles at the blade's leading edge deviates from a random distribution in Figure 12, the final calculated separation efficiency is only about 1% higher. Also, the length of the scavenge flow path of the IPS is varied to identify its effects on separation efficiency. When the length of the scavenge flow path is taken as 0.6∼2 times its physical length, there is no significant difference in the flowfield (as shown in Figure 13). Thus, no significant impact on separation efficiency has been observed.

To evaluate the deviation of separation efficiency caused by the variation of SCR, computations with SCR varying from 0.1 to 0.24 (nondimensionalized to [−1,1] in Figure 9) are carried out. During simulation, the mass flow rate of the core flow path is kept constant while the mass flow rate of the scavenge flow path is changed. Results show that the separation efficiency positively correlates with SCR, but the variation range is insignificant. The suction capacity of the core flow path becomes weaker when SCR is increased. Thus, more sand particles move into the scavenge flow path, resulting in higher separation efficiency. The variation range of the separation efficiency is below 1% when SCR deviates ±5% near its design value (16.9%).

Computation methods

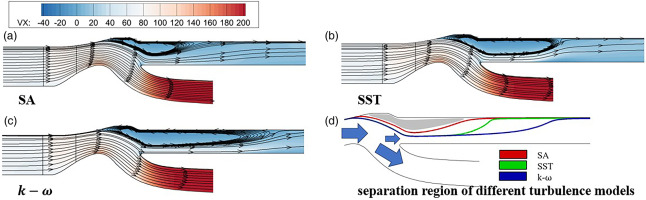

The turbulence model plays an important role in determining the pattern of the flowfield, especially in the separation region. The improved Spalart-Allmaras model, SST model (Menter, 1994), and

The particle–wall collision model is another critical part of the particle’s trajectory simulation. Calculations using models proposed by Niu (2017) and Tabakoff et al. (1996), with and without considering the effect of the randomness of rebound, are performed separately. The empirical relationship of collision velocity recovery coefficient

where V is the velocity of particles relative to the wall,

The separation efficiency calculated based on the above two different probability collision models only deviates within 1%, as shown in Figure 11. If the average collision model (without considering standard deviation) is used, the calculation accuracy will degrade, as pointed out by Hamed et al. (1995). Specifically, the separation efficiency of sand particles with a diameter bigger than 200 μm is significantly higher. When the sand particle’s diameter reaches 1,000 μm, the separation efficiency is about 4% higher. Because AC coarse sand is actually relatively fine (having an average diameter of 40 μm, as shown in Table 3), the separation efficiency is not significantly affected eventually. Different considerations of collision models lead to no significant deviation in separation efficiency, as shown in Figure 7.

Changing the sector angle of the scavenge flow path computation domain from 2° to 360° doesn’t significantly impact the flowfield and separation efficiency when the mixing plane method is used between interfaces. To further consider the influence of circumferential non-uniformity, such as the wake of the pre-swirl blade, the sector angle of the scavenge flow path computation domain is set to be the same as the pitchwise angle of the pre-swirl blade (20°) and direct interpolation method is used to transfer the flowfield data, resulting in 1% reduction of separation efficiency (as shown Figures 7 and 11). Thus, the data transfer method between the interfaces has little impact on separation efficiency in this IPS simulation.

Conclusions

The simulations of sand particles’ trajectory based on the gas-solid two-phase flow method in a typical particle separator are performed to identify the factors that affect particle separation efficiency systematically. The diameter distribution and initial position of sand particles significantly influence calculated separation efficiency, while the effects of other parameters are limited. Thus, the diameter distribution must be kept identical to the requirement, while sand particles must be released at the inlet randomly. For AC-Coarse sand, separation efficiency can be calculated as mass-weighted of several representative diameters determined by medium values of subintervals, and a number of 104 sand particles is sufficient to achieve sufficient accuracy.

The CSF of sand particles and SCR are secondary parameters that can be set to proper constants. When SCR deviates from its design value below 5%, the error of separation efficiency won’t exceed 1%. The CSF of sand particles can be set as 0.5, while relaxation to 0.35–0.7 would lead to an error range of about 5%.

The treatment of the intake device, length of the scavenge flow path, turbulence models and interface treatment methods used in flowfield simulation, sand particle release velocity magnitude, release velocity direction, and collision model between sand and wall used in particle-phase computation have minor effects on the separation efficiency. If computation methods and implementation are reasonable and credible, relatively flexible choices about these factors can be made in the simulations.

Nomenclature

Latin symbols

Drag Coefficient of Irregular Particle

Drag Coefficient of Spherical Particle

d

Diameter of Particle

D

Drag Force

e

Restitution Ratio

m

Mass

Mass Flow Rate

Total Pressure

Reynolds Number of Irregular Particle

Reynolds Number of Spherical Particle

S

Characteristic Area

Relative Velocity of Particle

U

Relative Velocity between Particle and Air

Position of Particle

Z

Ratio of Mass of Irregular Particle to Spherical Particle